Leading progressives in the US Congress recently joined a growing list of world leaders pushing to supplement GDP with a broader measure of human progress, an idea conservatives lampoon as “squishy indeed”. But this movement dates to Simon Kuznets, the Nobel laureate who invented the precursor to GDP to quantify US losses during the Great Depression.

Even Kuznets pushed for a higher standard, saying this crude tally of stuff bought and sold did not reflect a society’s well-being. In 1968 US Senator Robert Kennedy said gross output measures everything “except that which makes life worthwhile”, including the health, education and welfare of children.

Researchers have since proposed alternatives from Gross National Happiness to the Well-Being Index, the Malaysian Fuzzy Quality of Life Index, and India’s Green GDP. The US legislators are promoting GPI, the Genuine Progress Indicator, now the most serious contender alongside BLI, the Better Life Index endorsed by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

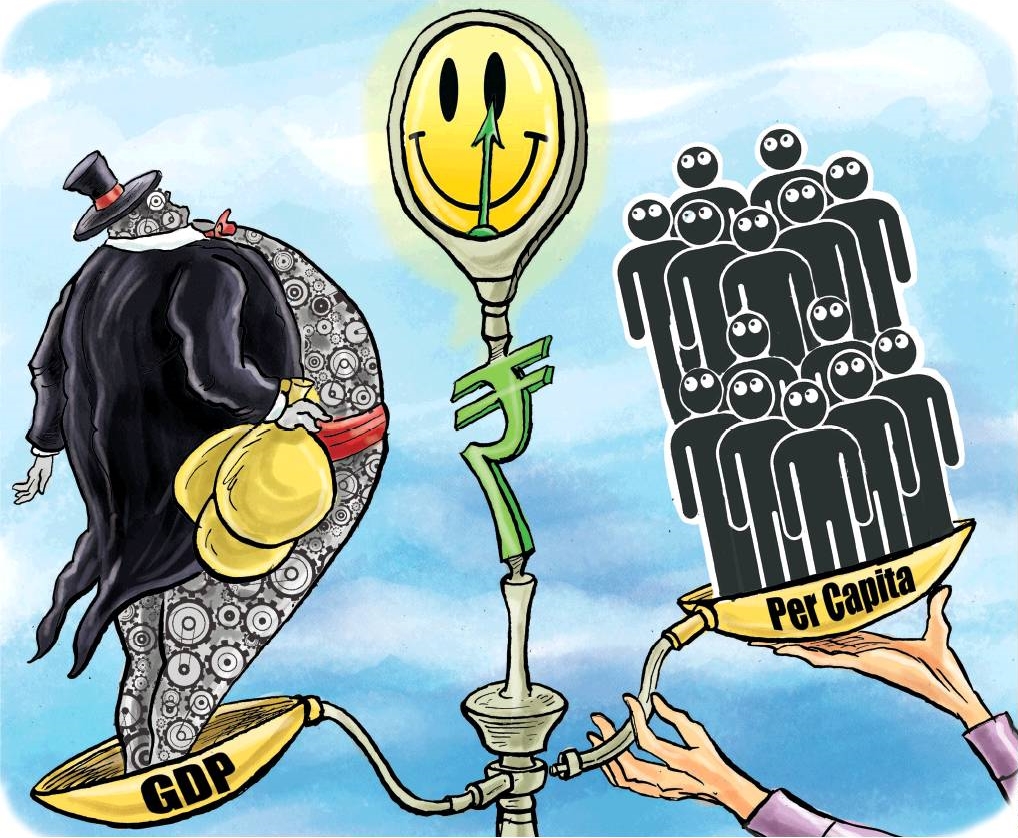

All aim to modify or replace GDP with social or environmental factors, or both, but disagree on the factors. It may be decades before the world settles on a new standard. As experts debate, a sense that rising prosperity is not lifting most of mankind is spreading. But an interim fix is at hand: Replace GDP with per capita GDP as the main target of policymakers and the key measure of progress.

Measuring GDP per person (or average income) reflects progress on many social welfare indicators reasonably well, and captures a threat that the new alternatives ignore: population decline.

Nations with higher per capita GDP tend to have higher life expectancy and levels of social support, lower infant mortality and poverty levels, less air pollution and corruption. Many of these measures are strong predictors of life satisfaction, which helps explain why richer countries tend to be happier.

The latest World Happiness Report ranks just one country with per capita GDP under $15,000 (Costa Rica) in the top 25 and none with per capita GDP over $15,000 in the bottom 70. The factor that best explains happiness survey results for any given country, say the authors, is per capita GDP.

Among emerging countries, those with higher per capita income also typically score better on the UN’s multidimensional poverty index, which includes quality of life measures such as access to drinking water, a solid roof overhead and basic assets like a bicycle. Critics of GDP can point to exceptions, but the basic rule holds: If a nation focuses on growth, development will follow.

India illustrates the point, to an extent. Over time, India’s gains on welfare indicators like life expectancy and infant mortality have been accompanied by rising per capita GDP. And as growth in average income started to accelerate after the turn of the millennium, India was one of the countries that made the largest strides in reducing the number of people living in severe multidimensional poverty, according to the UN. Nonetheless, India has been sliding down the happiness rankings and now stands 139th out of 149 countries. That is well below what one would expect for a country with a per capita GDP around $2,000, and may owe to rising concern over inequality and corruption.

Many people believe that beyond a comfortable income level, more money doesn’t add much to contentment. Yet among advanced economies, higher income does show a clear tie to higher happiness scores. The higher income Swiss and Norwegians are happier than the somewhat less rich Germans and French.

Advocates of moving “Beyond GDP” say that mobilising nations to achieve a dollar target enslaves governments to Mammon, at the expense of what makes life worthwhile. Many people sympathetic with this view, point to the case of Bhutan, which though relatively poor has often been feted as “the world’s happiest country”. Is it? Bhutan ranked 95th in the 2019 happiness survey and has since disappeared from the poll.

Critics of per capita GDP focus on what it misses, including the hot-button issues of inequality and CO2 emissions, but in seeking a more perfect measure they are resisting the urgent need for improvement.

Economic growth, a pillar of human progress, is under threat. As birth rates fall, the working age population is shrinking from Germany and China to Japan and Russia. Fewer workers mean slower economic growth, possibly with higher inflation. Total GDP captures neither population decline nor welfare, and still reigns thanks to inertia. A measure so deeply ingrained in the system is hard to drop.

But unlike the new alternatives, per capita GDP is available now in real time for most countries, and it’s more telling.

Consider future recessions. In nations where total GDP is shrinking, per capita GDP may well not be, if the population is shrinking more rapidly. Increasingly, slowdowns in total GDP will not be slowdowns in average income, or in the human progress that comes with it. Even as the pie grows more slowly, each person can get a bigger slice, easing social tension.

Adopting per capita GDP as the new standard would paint a less alarming picture of the global growth slowdown. It would ease pressure on politicians to generate growth faster than what shrinking labour forces will allow. Indirectly, it would promote the aims of those who want slower growth to limit climate change. And it would be a step towards the holy grail: a broad measure of human happiness.

(Published in the Times of India dated 11th November 2021)